The Artist

A Land of Every Possible and Impossible Colour

English artist Nora Cundell (1889-1948), along with her sister Violet and brother-in-law Charles Eaton, traveled to Arizona to see the Grand Canyon in 1934. Nora had read descriptions of the canyon and northern Arizona written by her friend J. B. Priestley, the English author and playwright. Priestley and his family made several visits to the Grand Canyon, the Vermillion Cliffs, Painted Desert, and Navajo country. His writings intrigued Nora enough to plan a trip to America to see those places for herself.

Nora’s plan was to first visit the Grand Canyon, but the canyon, unfortunately, was shrouded with what Nora described as a “thick sea fog.” Although disappointed, they decided to go down to the Painted Desert. At Cameron on the Little Colorado River, it was suggested that they should not miss Marble Canyon, about seventy-five miles to the north. Driving through the desert, Nora marveled at the array of colors. The hills were “rounded and fluted into the most fantastic shapes and of every possible and impossible colour—grey, brown, red, green, purple.” The cliffs were “tall, jagged and scarlet, and the hills were dotted with cedars, junipers, and an occasional hogan.” They drove through a sandstorm, with blowing sand rattling the outside of the car. Nora described the sand as being coarse and red, and noted that it stained water and clothing to the color of “weak tomato soup.”

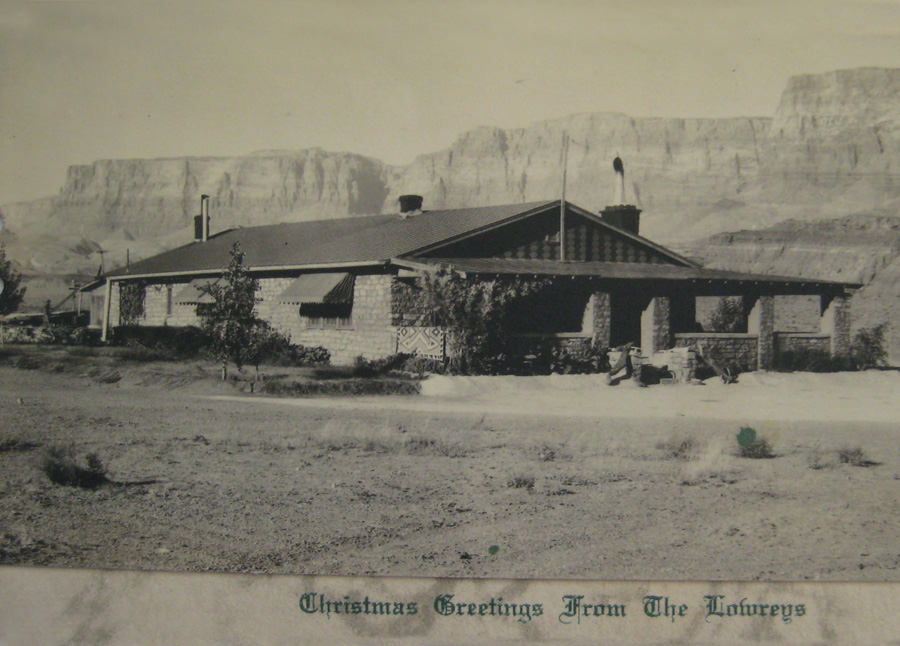

From 1934 through 1938, Nora came to Arizona, staying with Buck and Florence Lowrey at their lodge at the base of the Vermillion Cliffs. Courtesy of Harvey Leake.

Nora, Violet, and Charles crossed Navajo Bridge over the Colorado River and arrived at Vermillion Cliffs Lodge (today known as Mable Canyon Lodge) set in the barren desert and sheltered by a few cottonwood trees, along with a gas station and several cabins. Inside the lodge the main room had a huge fireplace and polished floors covered with skins and Navajo rugs. Comfortable chairs and books everywhere created a place that “looked more home-like than anywhere I’d seen for a long time.”

Further Dimmings, home of Nora Cundell, Dorney Village, Windsor, England. Courtesy of Telma G. Dufton

Hither Dimmings, home of Violet (Cundell) and Charles Eaton, Dorney Village, Windsor, England.

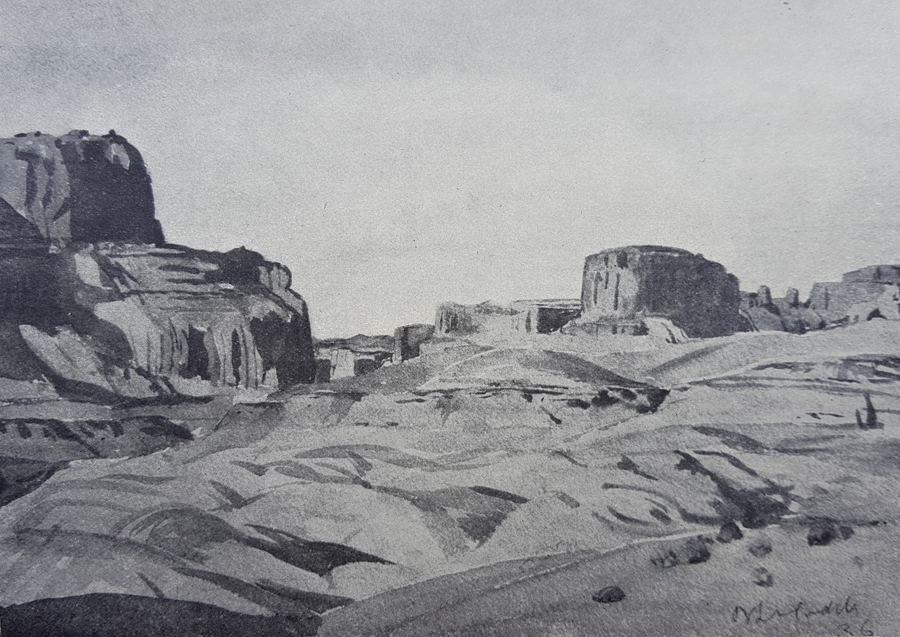

The Vermillion Cliffs, Arizona

Near Rock Creek

Unsentimental Journey, published in 1940, was the story of Nora's time at Marble Canyon.

As a Dream That is Past: Nora’s Last Stay at Marble Canyon

Paria Creek near Lee's Ferry, 1949. Photo by Editha L. Watson.

Nora Cundell, left, and Christina Klohr, right, 1947, Lee's Ferry. Courtesy of Bernice Klohr.

Nearly seven decades after her passing, this plaque still marks Nora's life, and her love of the Colorado River Country.